What’s the Big Concern?

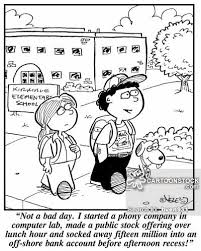

The most frightening apparitions of the future of education may very well emanate from the technology industries that are themselves seeing a highly lucrative market that has been largely untapped. This view of education as a business is becoming more mainstream as technologies, and specifically web-based technologies, continue to proliferate into education creating a market for consumers with a wide array of user-pay and free learning opportunities. However, many of the free online learning opportunities provide limited access to the educational resources offered of which, only for a fee, can be fully taken advantage. This is essentially how a for-profit business model pays token respect to the traditional ideals behind the right to education for all. But educators and their administrators are becoming complacent to these companies in a top-heavy bureaucracy that continues to funnel funds up and out of public and publicly-funded private classrooms. For many the idea of education has been generally defined as an inalienable right, an institution that helps to identify and support a stable society, and a necessary part of any civilization.

Article 26 of the UN Declaration of Human Rights states that education shall be free and compulsory at elementary levels and equally accessible to all on the basis of merit at higher levels. This is a lofty goal, but it reflects a level of humanity necessary to maintain the unspoken social order that communities rely upon not only to function but also to adapt to changing environments, to innovate, and to better care for the lives of everyone in the community. So, does educational technology not help in this way? What is wrong with re-purposing or expanding uses of technologies to enhance or provide new ways of learning? Will this lead to more harm against the altruistic values of education? The answer lies in the sources from which the technologies are promoted and sold as educational tools.

From Where Are Technology Trends in Education Coming?

A cursory examination of web sites promoting educational technologies and their “trends” reveals a staggering truth. There are countless sites disguising themselves as havens of education, even employing user-created content to surreptitiously sell an educational product or service to an otherwise unsuspecting student, scholar, teacher, or researcher, much in the same way that big pharma pays for third party research labs to publish less than 20% of their findings as positive articles, and promotes drugs. Here are a few examples of how technology is being sold to education:

“When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.” This quote, taken from the top of every page of Tech & Learning, whose “advisor” blogger, Steven Lahullier, attempts to identify the top 10 educational technology trends, is basically a disclaimer revealing that the blog post aims to secure more commission sales when clicking on links to purchasing sites. This kind of blatant consumerism has become so pervasive that most site visitors don’t even notice it or the ramifications that it represents. The blogger writes whats appears to be an innocuous article on emerging technologies in the classroom and readers are given the false reassurance that the author is being genuine by adding a short bio at the end describing him as an elementary school technology teacher and doctoral candidate from New Jersey. The author has posted three articles on the Tech & Learning site, but the site does not stipulate whether or not the author has received any kind of compensation for his contributions. It would interesting to see what kind of technology he is teaching at his elementary school. Scrolling to the bottom of the site however reveals that the company is “© Future Publishing Limited Quay House, The Ambury, Bath” in the UK, an enterprise whose services include “Advertising Solutions”, “Events”, “E-Commerce”, “Future Fusion”, “Digital [and] Print Licensing”, “Audience Insight”, and “Case Studies”. This is a company whose purpose is to brand and sell ideas and image to any market, in this case, education.

The International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE) blog site is another venue for the promotion of products and company-driven changes to education. It heightens the education industry’s side of buy-in through the setting of “standards” for implementation and practice of technology in education. It is also a promotional organization that publishes books, two peer-reviewed journals, a quarterly magazine, and an online blog from which one can find out their idea of what the “9 Hottest topics in edtech” is for them. Again, a cursory examination of their site reveals a fairly transparent business model as can be read in more detail from their annual report page where they collaborate to assist profits from the sale of “a host of powerful new programs and products, including ISTE Certification for Educators, ISTE U,” to name a few.

“eLearning Industry” is another publishing company that has created a community of professionals who support technology in education so much so that one can pay for an “eLearning Professional Badge”. This company exists in much the same way as Hollywood product placement agencies exist, to act as go-betweens for the placement of products and services to be placed in movies and sometimes demonstrated or even spoken about by actors, only in this case the professionals themselves (i.e. teachers) sometimes pay for the privilege of promoting and instructing on the use of the technologies they like to use in their educational settings. Two blogs from this site promote technology without going into any detail on its pedagogical efficacy. One blog’s first-touted edtech trend is whiteboards, a device that has fallen into storage in my school since the advent of more powerful and interactive cloud-collaborating tools usable on smartphones or tablets.

Lamda Solutions will not even identify its author on a blog titled The Biggest Education Technology Trends for 2019. It is clear that this is a for-profit business offering services that aim to help educators create revenue-generating eLearning management systems. One can basically pay for set up of their own online school with full support in the form of Lamda’s marketing function Suite, its open-source Learning Management system, and its award-winnng Analytics system to help maximize profits. This site hearkens educators to consider how well from a business perspective educational technology fits with online learning. But how does this ensure the quality or usefulness of what is learned?

The content marketing manager Quin Parker is the writer of yet another educational technology trend blog. The company for which he works, Top Hat, purports to be the “best learning management system”, and a quick glance through its promotional page reveals an impressive array of features that are included in the blog. In this case, it may be easily alluded that TV’s infomercial’s online incarnation is the blog or the vlog where content creators can earn the prestige of becoming “influencers” as can be identified on YouTube, LinkedIn, and other social media sites.

None of these blog examples speak to a higher purpose or value of education, since any value that may initially be given to them is thwarted by their underlying function to represent a business interest. This feeds the cynical view that the great majority of educational technology writing online is simply a thinly veiled practice of corporate business and product promotion.

Have Online Journals Been Infiltrated by Big Business, Too?

A 2014 article in TechTrends attempts to bring some form of academic rigour to the subject of what the future of technology holds for education. The article perhaps represents the most insidious use of pseudo-academic writing to sell its readers on the idea that it presents a set of needs for education to survive into the future of a globally connected community of learners. However, TechTrends is one of many journals owned by publisher Springer and its parent company, Springer Nature offering researchers products and support in the form of journals, books, data bases & solutions, and platforms including the prestigious nature.com. Their brands include Scientific American, Adis, J.B. Metzler, and nature research. This is a publisher first, then a disseminator of new and emerging knowledge. The article itself lacked a cohesive flow, perhaps because it never ventured to answer directly its owns posit of “the needed transitions in knowledge and skills”. “[I[indicators of our growing interests in mobility, improved quality, and personalization, all happening within our increasingly global community” hardly come close to identifying the present gaps in education the article aims to fill with technology. This is not backed up by any evidence. If identifying instructional gaps by offering three anecdotes about robotics, a school nurse, and how to add email recipients is the basis for this article, then it logically follows that the examples of technologies in decline are non-evidenced and misleading. For example, contrary to the article’s assertion, large bookstores have become larger by being bought out by big chains and network TV is simply shifting its business model to a subscription-based form as well as continuing the trend of being conglomerated by larger entertainment corporations such as Disney and Time-Warner. The authors do not seem to understand the vantage point they stand upon from which they try to build the rest of their article. No evidence is given either for their contention that books sold as e-texts are out-selling hard copies and paperbacks combined. Other popular press articles state that printed book publishing has continued to enjoy growth in almost every genre. The physical experience of reading the printed page is as popular and celebrated as it ever was. In my own experience, my school library continues to grow, and more students read for leisure now than ever before.

Perhaps the single most important question of this article is the admission that “we might be missing some of the underlying bits of important knowledge needed to carry us forward in a digital era.” Taking this idea in a broader sense reveals the writers’ own gaps in the deeper values of technology in education.

The authors go off on a tangent of sorts using an article from CNN Money (2012), the “7 Fastest-Growing tech companies” to identify “Technology Growth Areas”. The CNN article’s figures, however, reflect highest profit figures for single companies, not most growth in general technology-based areas as the section title implies. For example, Baidu China’s search engine was developed as a Chinese state-regulated version of Google and although it is public on the NASDAQ worth 14.9 billion US, it is registered in the Cayman Islands to avoid any US or International taxation regulations. Using skewed profit figures like this to identify technology growth areas does not fit well with education unless education’s purpose has a purely profit-driven purpose as well.

The article’s academic tone falls flat at this point “[T]alk about seductive and personalized, just shake your phone and it will locate similar stations, how sweet is that?” Is this article selling apps? The authors go even further by using business terminology in place of social terminology describing training and education as “knowledge-based economies”. This firmly establishes a tone that devalues education as a pillar of society and makes it an opportunity for profit.

The authors continue to inadvertently express their confusion about technology by quoting another academic: “To have mobile learning work well, power has to shift from instructors and managers to the learners themselves” (Woodill, 2011, p. 165)”. Even Woodill misses the obvious that this is not only a notion of how to best use mobile learning networks, but also how to best learn and teach in general. Even Socrates put the student at the centre of their own learning by using the art of questioning (e.g. Socratic Seminar). Many education theorists put students at the centre of their ideal model of education.

In making assumptions about the globalization of education, the authors state “Globalization has accelerated the exchange of ideas and perspectives thereby increasing the overall knowledge base.” This is a false statement. The increase in exchange can also simply mean the increase in the number people exchanging basically the same amount of knowledge. Just as there is a likelihood of increasing the overall knowledge base, there also the likelihood of homogenizing knowledge on a collective level to suit the needs of those who hold the power to curate knowledge bases.

A short section entitled “Objectives for Learning” is a simplified reiteration of many education boards’ mission statements that include the equipping of knowledge and skills to students’ successful learning. This section does little to help refine the purpose of the article, but the following section “Flipped Classroom” points readers in the underlying direction. Essentially, the flipped classroom is an ideal educational structure for a lucrative online business that does not require an instructor with practical knowledge or skills. For a more detailed reasoning of this opinion, please read my brief blog on Backward Planning.

Several points made in the concluding section of the article are also worth arguing. The point is made about online learning management systems that “[R[ather than guessing what students have learned, it is statistically analyzed at the individual level to ensure it is happening through personalization.” This is an old skill of a good teacher who checks individual’s learning and modifies it for each student, but an excellent teacher will modify what is being taught as well to suit the student’s need. This approach to assessment may be part of the next generation of algorithms used by Artificial Intelligence (AI) in place of generalist teachers who can be easily automated. I believe this form of “educational technology” to be a real threat to the future of Massive Online Open Courses (MOOCs) in the same way that reality TV producers can profit much more with the removal of writers and actors.

Again, quoting another researcher, the authors try to insinuate that education is essentially job training: “Am I learning? Am I becoming a smarter more innovative human being? That’s what’s going to serve you in the real job market of tomorrow. By the time the corporation has told the city college what skills it wants from its future workers you are going to graduate and those skills will have changed anyway” (Rushkoff, 2013, p. 3). This illustrates the false assumption that education’s primary role is to create a flexible but viable workforce for the “job market of tomorrow”. Education in its pure form should be altruistic, filled with self-discovery, and enrich the appreciation, acquisition, and expression of knowledge, culture, language, and the arts if it is to evolve out of the industrial model that has been reshaped from its original form into a market that serves corporate interests.

A Way Back to the True Values of Education

Of course, the use of technology in education has many benefits and can certainly help prepare students for adult life. The fundamental nature of education is being challenged by the proliferation of corporate interests in what has always been a challenging but potentially highly lucrative market. The “knowledge-based economy” as so aptly described in business-like terms is a real threat to the value of basic education on a global scale. The pressure on public, government-funded education systems to purchase the services of privately-owned learning management systems, full-service learning supports, analytics, e-learning environments, and eventually fully automated online schools will only increase in the future as the nature of most democratic bureaucracies look to have front-line workers do more with less funding. To exacerbate the problem, multinational corporations exert their influence from countless directions, often employing the expertise of education professionals themselves. These professionals may not realize they undermine their own security as they convince themselves offline that no amount of AI will replace the face-to-face interaction between teacher and learner. The burgeoning industry of educational technology is falsely recognized as the heralding force of a paradigm shift in education that will meet the future needs of a creative, problem-solving, innovative, team-playing workforce. Look closely at Google’s workforce, not the image or architecture or the environment that disguises the masses of workers not being paid a living wage in countries where employment standards do not exist and human rights are paid lip-service. That is where the majority of Google’s employees work. If Google is at the leading edge of new and emerging job markets, then educational technology is doing a good job of following step by providing consumers with more “certified” education options at prices for the select few. The recent scandal of celebrities paying for children’s SAT scores illustrates this point.

What is needed is a great shift in a democratic sense that re-instates the core values of education as outlined by the UN Declaration of Human Rights. Governments need to be excised from corporate corruption so that public education is truly public again. Legislation to protect individual data rights might be a first step to regaining an original intention that the internet should be open and accessible to all. The continued development of free, downloadable, open source code will help keep education from being monetized and becoming a commodity. I teach students, not the use of educational technology. As a digital film, photography, and acting teacher, I use technology extensively in my classes, but students know that the subjects I teach are about them and how they express themselves through the technology they learn to master. How we learn about ourselves and the world through broad learning that offers deep investigation and illumination by specialist teachers might offer a return to ancient and essential ways of learning, but may also save the very foundational values upon which education stands as a feature of a civilized global community.

Leave a Reply