Folke adjusts himself in his “high chair” and flips through his observation notes. Unseen, Isak, Folke’s subject, has drilled a hole through the ceiling above and is also looking at the observation notes. He inadvertently calls attention to himself by shining a flashlight through the hole so as to see the notes more clearly. Folke looks up, the light immediately goes off, and the hole is carefully plugged so as not to arouse Folke’s suspicion.

This scene is from the 2003 film Kitchen Stories by Norwegian director Bent Hamer. in it “(a) scientific observer’s job of observing an old cantankerous single man’s kitchen habits is complicated by his growing friendship with him. ” (retrieved from IMdb, Kitchen Stories). The film is typical Scandinavian fare, replete with sparse dialogue that is at times harshly blunt, reflecting the life and landscapes of those courageous enough to make it their home. To the uninformed audience, it is a light comedy, thoroughly entertaining as one complication after another brings the story to a tragic and touching close that leaves its audience revelling in the intricacies of relationships that seem to grow by chance alone. The film informs as it unfolds and a cursory reflection on it reveals a thickness of layers of personal, psychological, methodological, and social commentary set in post-war rural Norway. The film contains many sticking points relevant to research methods, methodology, and the ways in which we learn about ourselves.

Kitchen Stories – Trailer (Kitchen Stories Trailer)

In the heart of the film sits a rhythm wherein there is a contraction and inflation of observation that is reflexive for all of the main characters in the story. There are layers of observers all watching and reacting to each other and to themselves. This puts a critical lens on the premise of the film, a scientific study to observe the movements of single men in their kitchens, and the audience becomes witness to the shift from objective intentions into the chaos of inevitable subjectivity.

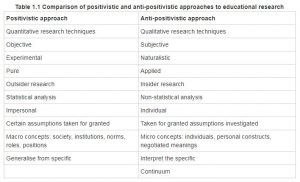

In the context of research methods and personalized learning, this film introduces some very important implications in that it exposes issues of objectivity and the value of scientific method as it is applied to real people in real situations, not unlike the research that is conducted in educational settings. There is a large body of educational research that has moved away from what was considered to be the only valid type of research in academe. Qualitative research, as it relates to education, has perhaps taken the driver’s seat and in essence has accepted that the variability in educational settings cannot meet the demands of the deductive form of quantitative research. For the majority of masters students who are not going on to PhD studies, the qualitative approach makes sense but does not imply that any less rigour is applied. The rigour is simply of a different type as illustrated by Clive Opie (2004) in Table 1.1 below.

From Opie, C. (2004). Doing educational research: A guide to first-time researchers (Chapter 1, p. 8).

The anti-positivistic approach takes into account the inability for the researcher to be completely separate from the researched within a real-world context. Only in a controlled laboratory setting where all variables can be accounted for can objective data attempt to be collected as in the opening scene of Kitchen Stories (Hamer, 2003). Positivistic research using scientific experimental methods rarely reflect the real world of education where human interaction is dependent upon innumerable variables. McMillan and Schumacher support the argument for using qualitative methodologies in education by stating that “although objectivity is important in all research, it is more difficult in research on humans”. (McMillan & Schumacher, 1984 as cited in Opie, 2004, p. 8). This is just the tip of the iceberg as far as understanding the the true nature and depth to which subjectivity is infused in all research and any observation for that matter.

It is ultimately impossible to remove the observer from the observed. Even in today’s technology-rich environments where the controversial use or abuse of surveillance is celebrated in “reality show” entertainments like “Love Island”, the content of what ones sees is dependent not only upon where but what the camera is leaving out of its frame and how much and in what style the director and editor choose the content to be seen by the audience, but also what the observer’s eye chooses to track and take conscious notice according to her/his own tastes, likes, dislikes, personal relatedness to what is being shown, and social-political-cultural context in which it is shown. In this light, it is impossible to find objectivity in anything that is observed. This must be a painful realization for positivistic clinicians. There is a kind of suffering inherent in the realization that the observer has been constructing the way in which the observed is perceived. Kitchen Stories revels in the cyclical nature of observation and takes the audience on a path to deconstruct the very idea of observer and observed. This brings me to my secret passion for philosophy and deep learning for which I believe all students have a burning hunger to taste and feel the joyous pain of self-realization.

In a classic work of Krishnamurti (1969) titled Freedom From the Known, at the end of the rabbit-hole of the observer watching the observed who watches the observer (ad infinitum) is a transcendent awareness. The point he makes is relevant to us as researchers because he explains the source of the conflict we feel when going deep into our research, and essentially into what the ultimate meaning is that we are trying to observe or find. Krishnamurti states:

One image, as the observer, observes dozens of images around himself and inside himself, and he says, ‘I like this image, I’m going to keep it’ or ‘I don’t like that image so I’ll get rid of it’, but the observer himself has been put together the by various images which have come into being through reaction to various other images. (p. 96)

In other words, what we see is a product of the context upon which we have built our own sense of identity.

So we come to a point where we can say, ‘The observer is also the image, only he has separated himself and observes. This observer who has come into being through various other images thinks himself permanent and between himself and the images he has created there is a division, a time interval. This creates conflict between himself and the images he believes to be the cause of his troubles… …but the very desire to get rid of the conflict creates another image.

Awareness of all this, which is real meditation, has revealed that there is a central image put together by all the other images, and this central image, the observer, is the censor, the experiencer, the evaluator, the judge who wants to conquer or subjugate the other images or destroy them altogether. The other images are the result of judgements, opinions and conclusions by the observer, and the observer is the result of all the other images–therefore the observer is the observed.” (p. 96)

[and]

It is not a superior entity who becomes aware of this, it is not a higher self (the superior entity, the higher self, are merely inventions, further images); it is the awareness itself which has revealed that the observer is the observed.” (p. 97)

This conflict within the observer can be described in different ways. Some scholars have seen this conflict as an unhealthy attachment to things, accomplishments, and objects that unquestioning people use to form their sense of identity and purpose. Sean Steele (2014) uses a similar concept of material gain in a spiritual vacuum in his criticism of education and his expression for the need for deep Dionysian learning:

And just as we use our “summative” assessments to distinguish and reinforce the supreme reality of the egoistic self, so too do we design our “formative” assessments and pedagogical practices to strengthen our psycho-mental aptitude, to redirect another, and generally to shape the individual ego-selves of students under our tutelage for their future successes — as if this were the real nature of genuine or deep education. (p. 9)

It is a deep-seeded fear of publicly revealing our connectedness to each other that prevents the kind of realizations that spark true life-long learning in not only the students we teach, but also in ourselves in the presence of our students. Realizing the observer is the observed removes the pain of conflict and makes us vulnerable to each other, but the lesson of letting go of our attachments, or, as Krishnamurti puts it, of realizing “an awareness that has become tremendously alive.” (Krishnamurti, J., 1969, p.98) should be ongoing and should be embraced not only in our drama classes in the safety of a carefully trust-built environment, but in all of our teaching and researching if we are to affect lasting positive change. The notion of the objective observer is moot in the awareness that what is seen is what is seeing, that who we are is everything of which we are aware, and that our actions are ultimately void of conflict, void of not-knowing, and are beyond the need for understanding.

The curiosity that drives us to be researchers and teachers is partly in taking ourselves and our students through this journey of deep reflection, awakening, and awareness that is life-affirming and transcendent and impossible to point out or to measure, but connects us to immortality we all share.

References

Hamer, B. (Writer), & Hamer, B. (Director). (2003). Kitchen Stories [Motion Picture]. Sweden: BulBul Films.

Krishnamurti, J. (1969). Freedom from the Known(M. Lutyens, Ed.). New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Opie, C. (2004). Doing Educational Research: A Guide to First-Time Researchers. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Steel, S. (2014). On the high school education of a pithecanthropus erectus. The High School Journal 98(1), 5-21. The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 5-21. doi:10.1353/hsj.2014.0011

Recent Comments