The very complex issue of understanding how and why we teach in a system that is steeped in all kinds of markers that point to settler ways of working and learning is incumbent upon this next generation of teachers and scholars to unpack, to question, to compare, and to contextualize with their personal stories. How can such a heavily bureaucratic settler system of education and scholarship change to be more open not only to Indigenous ways of working and learning, but to the rich traditions of all cultures that continue to evolve? Is social justice a door that can open a way for decolonization to happen? Can the dominant culture put on a pair of Indigenous glasses to bring a new set of actions that will evolve the learning world to be all-inclusive?

I thought about inclusiveness in our learning institutions and how the idea has even changed the moniker of our Special Education department into the Inclusive Education department. But has this been a change in name only? Surely this was not the intention behind the name change. Policy changes have come with the name change across our school district, but the actions of many of my colleagues have remained the same. I taught a media course a few times with a group of Inclusion (formerly Special Ed.) students and continue to accept these students with open arms in all of my classes. At one point, I reached a realization that seemed like a crazy idea, and one I did not have the confidence to act upon. I thought of reversing the Inclusion students in a way by putting a couple of them in each of our Planning 10 (now called Career Life Explorations) classes and having all the other students go through a typical day at school with them, learn through their eyes, understand the way they understand, hear their personal stories first-hand, and present their findings to the class about how our school system is helping them and failing them at the same time.

The same could be said for Indigenous Education as it relates to the majority of my colleagues’ classrooms. Most of us pay lip service to the idea of including First Peoples’ Principles of Learning in our lessons. I credit Dr. Shauneen Pete for finding a concrete way to answer the call to action beyond putting the poster up in the classroom and pointing to it during a “teachable moment”. Social justice can be explored in every subject and it can be the “can opener” to decolonizing our learning environments. But how does this tie in to Inclusion? I thought of a form of Reverse Inclusion that turns out to be already in practice in many schools. You can read more about it here: Issues of Reverse Inclusion . What about Reverse Colonization as a form of exercising social justice? Well that turns out to be a pretty old subject, too, and one that has had its drawbacks. Here’s a 2-minute video to show that history has been there (in poetic form):

Valerie Bloom reads ‘Colonization in Reverse’ by Louise Bennett

To connect this phenomenon of reverse colonization to my own experience, I was first exposed to Indigenous culture at a very young age by my mother, a German immigrant, who passed on her ideas about North American First Nations Peoples through her own primary exposure to German adventure stories written by Karl May. Karl May wrote stories of the “wild west” which became a first exposure of the New World to many Europeans, especially children like my mother. His was a pioneer in bringing this kind of historical fiction to life. A cursory exploration of this “story-telling” helps to explain the stereotypes of Indigenous Peoples that continue to pervade the dominant white culture even to this day.

Karl May (Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

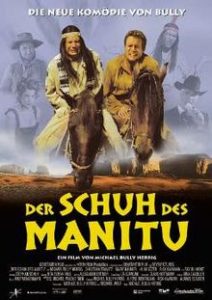

©2001 Constantin Film AG

Karl May embellished and dramatized settlers’ history, essentially bastardizing the Indigenous history of North America for the entertainment of the European masses. Indigenous culture was “colonized” to satisfy the European hunger for stories of the “civilized savages” and their strange customs and “costumes”. ” In 1880, Hagenbeck dispatched an agent to Labrador to secure a number of Esquimaux (Eskimo / Inuit) from the moravian mission of Hebron; these Inuit were exhibited in his Hamburg Tierpark.” (retrieved from Human Zoo ). Just to instill the shock of this, the word “Tierpark” literally translates to “Animal Park”. There was no outcry then, because knowledge of Indigenous cultures was so new and limited. This historical context goes a long way to explain how we have gotten to the place we are now. There is a long history of all branches of science and study getting it wrong and making mistakes that in today’s world would be beyond unethical and most likely illegal.

There is a virtual cacophony of voices calling on the institution of education to act, to re-educate ourselves and each other, to embrace a new level of unconditional cross-cultural respect. It is a call to find a deeper kind of relevance for the traditional structures and content of knowledge that we impart by using “other”-traditional ways . Our imperative now is to reciprocate by ensuring our teaching and research will benefit all invested parties. We are being called out to act responsibly with the privileges that we have been born with and those that we have worked to attain and place them properly within the First Peoples’ ways of knowing and learning. Underlying all of the voices is the call to build new communities, to keep the conversation going, and to nurture our relationships in the ways of the Indigenous ancestors who came before any of us. (with reference to The Five R’s for Indigenizing Online Learning: A Case Study of the First Nations Schools’ Principals Course)

Let’s begin by embracing the dialectic within ourselves, whether it be a “trickster” like Shauneen Pete’s “Coyote”, or a classic Socratic questioning voice, who challenges us to change our perceptions, and then ourselves, and then the world we create around us. It’s time to unpack our personal stories of the spirits that haunt our collective conscience, give them the recognition and respect that they deserve, so that all of us can move forward together.

Recent Comments