Above photo retrieved from: Paul Stacey-Executive Director at Open Education Consortium

Reactions to: Public Comment on Educational Videos: Understanding the effects of presenter gender, video format, threading, and moderation on YouTube TEDtalk comments ( http://tinyurl.com/yyk5dnrw )

Sentiment is complex and difficult to measure as a reaction to video in isolation of personal context. The way someone feels or thinks about a video is contingent upon many factors not the least of which includes socio-economic status, possible trauma, family history and culture, personal attitudes informed by experience, physical conditions both internal and external, level and quality of education, time of day, etc. This was not considered in the study and would have caused the researchers to calculate far too many variables for any level of reliability to be accepted. The study should therefore be looked at through a qualitative lens if possible.

Studying comments on videos is untenable in this day and age of bots and users who only post comments to direct the reader to their own channel in a popularity game of monetized advertising space. Many comments have nothing to do with the video at all and are purely self-serving. There are several more factors when trying to be educated by video comments.

Moderation may be an external pressure for the commentators to be authentic, especially when an online persona is a permanent record of one’s character and attitudes. Anonymity becomes a shield from which the darker side of the web hides behind as was rumoured and misreported by Mark Zuckerberg’s failed Artificial Intelligence experiment he conducted on Facebook (the real story about Facebook’s AI experiment ). Some reports revealed a language and culture of commentary ubiquitous on the internet that showed how insensitive, decadent, and unmannerly many users are on social media platforms. However, forcing transparency of identity may also affect sentiment depending upon the commentator’s own attitudes toward online privacy and their actions around it.

The format definitely affects sentiments in that “reposting” or “linking” is a form of showing positive or negative interest in a video that then becomes, in a sense, a descriptor of the person and reveals her/his/their likes, dislikes, or mood. It may also reveal a potential form of laziness for not creating an original video or response video. Poor format such as low quality picture or audio also will affect commentary results, most likely in a negative way that can be the fault of a poor internet connection, throttled bandwith, or electro-magnetic interference.

Gender bias online is a clear reflection and perhaps more transparent illustration of gender inequality in the workplace and the community at large. This issue is particularly unchecked online as almost every space is co-opted by advertising which, for the most part, perpetuates myths of sexualized behaviours and attitudes to entice purchases based on skewed lifestyle choices rather than product or service value.

To focus on the study’s data collection and analysis, a question of missing data is raised. The study used SENTIStrength admittedly which presented an issue of validity due to coder-agreement using only 3 human coders. Coding is inherently biased by the very intention of getting a software to produce consistent results where key variables reflective of the real world would be impractical to incorporate into the programming itself. SEM (structural equation modelling) as a framework dealt with missing data by relaxing the multicollinearity assumption using another technique called FIML (full information maximum likelihood). It was explained that this was a more robust method than using listwise deletion or mean imputation. In either case, however, this reveals that missing data was necessary and had to be accounted for in some way to provide some form of quantitative validity to incomplete data sets that had to be justified for an otherwise qualitative and subjective study of online video comments.

Talk topics would have certainly influenced the comments. The scale of reaction would have also been influenced by the abstractness of the topic. Quantum molecular biology, for example, would elicit much less emotionally-loaded comments than the rights of Neo-Nazis to hold parades in Jerusalem.

The study summary focused on negative comment effects that may be reflective of the unspoken sentiments that exist in real life situations but are self-moderated. This might reveal the clear distinction between the civility needed for face-to-face interactions and the “protection” that hiding behind a screen and a keyboard somehow affords. A control to measure this difference may have been to conduct the experiment simultaneously with a TEDtalk and incorporate live audience data.

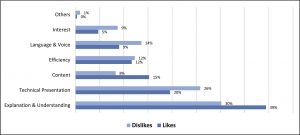

A more comprehensive study of sentiment toward online videos included parameters beyond “like” and “dislike” data collection to explain the sentiments of university students who watch educational online videos.

(from Shoufan, Abdulhadi 2019. What motivates university students to like or dislike an educational online video? A sentimental framework, Elsevier, Computers & Education, Vol. 134, pp 132-144. http://10.1016/j.compedu.2019.02.008

Online learning is as individual as each one of us. To try to make generalizations about how people react to online learning videos proves to be very difficult and may not be as quantifiable as this study attempts to show. Where we go to learn also depends heavily on who we are as much as what we want to learn and where we go online to learn it. How the majority of us interact as online avatars and not our whole selves has the potential to create a dangerous duality or multiplicity within ourselves.

Leave a Reply